It seems my New Year’s resolution to write blog posts more often has been quite quickly abandoned (but is it really a New Year’s resolution if you don’t actually fail to follow through, and realize there is no magical self-motivation that appears with the change of a number on a calendar?) I’m already well into my second semester of grad school, and I’m drowning in readings and work. Luckily, all my new classes are interesting, ranging from Elizabethan women’s writing, comparative rhetoric, and contemporary political novels—so hopefully I get to talk about some of the things I’m learning in class in other blog posts. It’s touching how bottomless human hope can be despite constant failure.

Today though, I want to return to something I worked on last semester. A final paper I wrote last semester explored the different Asian freaks on display in American freak shows during the nineteenth century, through a lens of Asian American studies and disability studies. Because I was fascinated about what I found, I thought I would share a little about them (I didn’t know about these figures before my paper, so hopefully someone else gets to learn about them for the first time as well). I’ll try to introduce these figures in general without going into too much detail about the arguments in my paper, because I hope I can further my project or potentially seek publication for this project in the future. In short though, I argued the possibility of what I call a crip kinship that these Asian freaks were able to facilitate through their disability/deformed bodies, which allowed them moments of identification that crossed social and racial boundaries.

Before I go into each individual freak, I want to give a little background about freak culture because I would hate to sound condescending or disrespectful to these figures. In the class I wrote the paper for we had to think a lot about how to give back agency to the freaks, when they were often taken advantage of and put on display for their physical differences to highlight their monstrosity (I’m not using the term “freak” in a derogative manner as we might understand it today. There is actually a lot of scholarship about freaks and some even theorizing how embracing the label can be empowering. Check out scholars like Garland Thompson, Robert Bogdan, and Elizabeth Grosz who all have good books on freak culture). These people, ranging from bearded ladies, giants, and those missing limbs or with unusual body proportions, were put on display on freak shows for the public to enjoy—an enjoyment that stemmed simultaneously from disgust and wonder. Although some of these freaks were paid well, they were still gawked at and unable to live private lives. From the various men who tried to profit off freak shows, P.T. Barnum was the most infamous of the freak show managers. He’s the subject of the film the The Greatest Showman, which I haven’t watched but feel hesitant to do so given the celebratory nature of the film. His obvious greed and lies that went into crafting narratives for the freaks visible from historical records mean we should be careful not to glorify him and his supposed genius. Yes, he was a great businessman, but that doesn’t mean he was morally good! (As an example, he purchased the slave Joice Heth as one of his early exhibits and claimed she was over 160 years old and a nanny for George Washington. He made up several hoaxes to increase the hype and eventually subjected her to an autopsy after her death, a common practice for these freaks who weren’t left alone even in death). Luckily, freak shows were deemed tasteless and began to die out past the 19th century, although we could argue we continue to have fascination with invading the privacy of certain individuals through modern day spectacles like reality tv shows.

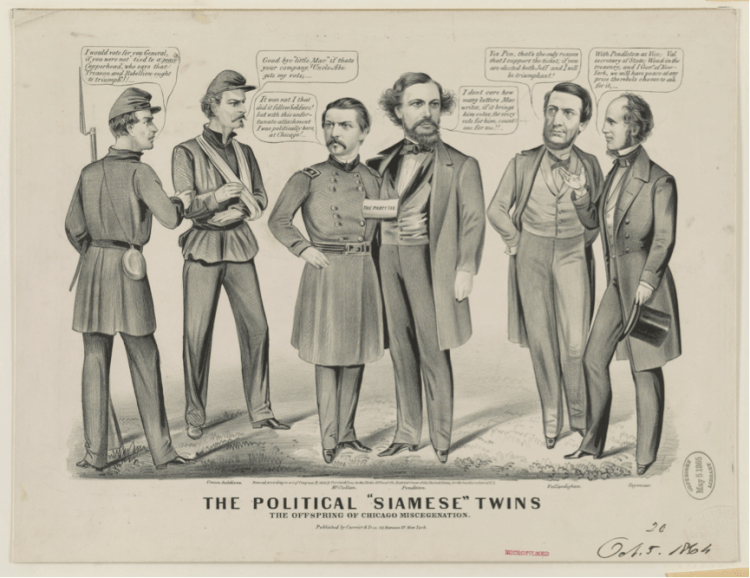

These freak shows, while seemingly for pure entertainment, made a huge impact as America was only just beginning to forge itself as a nation. They were tied to the formulation of nationhood and societal categories, from race, economic class, and heteronormativity. Stories were fabricated for each freak, and people like P.T. Barnum was careful to label certain freaks as savages and un-American based on the nature of their physical difference—even when they had in fact been born and raised in America. In contrast, freaks like Tom Thumb who enjoyed popularity as a man of elegance and class was associated with England, then quickly claimed as American as his success continued. Lower class workers and immigrants made up the bulk of the audience who paid to see these shows, with the consolation that they were superior to these freaks—that they were normal citizens by contrast. These freaks made their mark on American cultural production that continues to this day. Ever heard of the term “Siamese twins”? This came from Chang and Eng, who were ethnically Chinese conjoined twins brought over from Siam to be displayed. They actually went on to break away from their manager, and obtained American citizenship during a time Asian immigrants were scarce and definitely not granted citizenship (this was before the Civil War, and in fact during the war newspapers often used the conjoined twins as a symbol of the North and South who needed to reconcile and accept their union. Given how racist American society was at this time it’s astounding these Siamese twins were used to champion American nationhood and unity). They even owned slaves and had 21 children altogether, and their descendants still have annual conventions today. While it’s problematic they owned slaves, this just shows how they wrote themselves into white citizenry and how artificial the legal and cultural criteria for citizenship can be. References to Chang and Eng appear in literature everywhere, from stories by Mark Twain, an allusion in Moby Dick, and of course in a lot of Asian American literature that grapple with a hyphenated identity or feelings of double-consciousness. Chang and Eng, along with other Asian freaks, affected both American history as a whole and Asian American identity in ways that we aren’t even aware of but are all around us. After reading about Chang and Eng, I began to see them mentioned everywhere (Maxine Hong Kingston and Cathy Park Hong both mention them in their work!).

For further context about why these Asian freaks were so significant was that although they were subject to alienation, they were generally and uniquely viewed positively amidst growing hostility toward Asians. By positive I don’t mean they escaped racist stereotypes and condescension, but they faced relatively harmless curiosity in comparison to the phenomenon of the Yellow Peril brewing in the nineteenth century. The Yellow Peril was the fear of invasion of Asians in the West, a fear so strong that by 1882 the U.S. passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, the first time the nation tried to keep out a particular group of people through legal means. Asians were portrayed as scheming, immoral, and sexually deviant. Asian immigrants were depicted as parasites, and Asia began to be associated with disease and disability (for example, along with the parasitic imagery that apparently threatened to make America sick—I can pull up direct sources if anyone is particularly interested—Down syndrome during this century was labelled Mongolism. Although Asian Americans are often deemed the “model minority,” a problematic way of thinking in itself which you can read more about here, it’s important to remember Asian American history and the struggle for acceptance). In line with the tendency to link Asians with disability, most of the Asian freaks were so fascinating because they were deformed, if not disabled. Yet despite this negative association with physical difference, I think these Asian freaks tried to imagine something other than the dystopian vision Westerners had of Asians taking over (the term Yellow Peril is first thought to be coined through a prophetic dream by Kaiser Wilhelm II, which he commissioned into a painting). The Asian freaks were able to help the public imagine a coexistence with Asian bodies amidst growing denial this was possible, much less desirable.

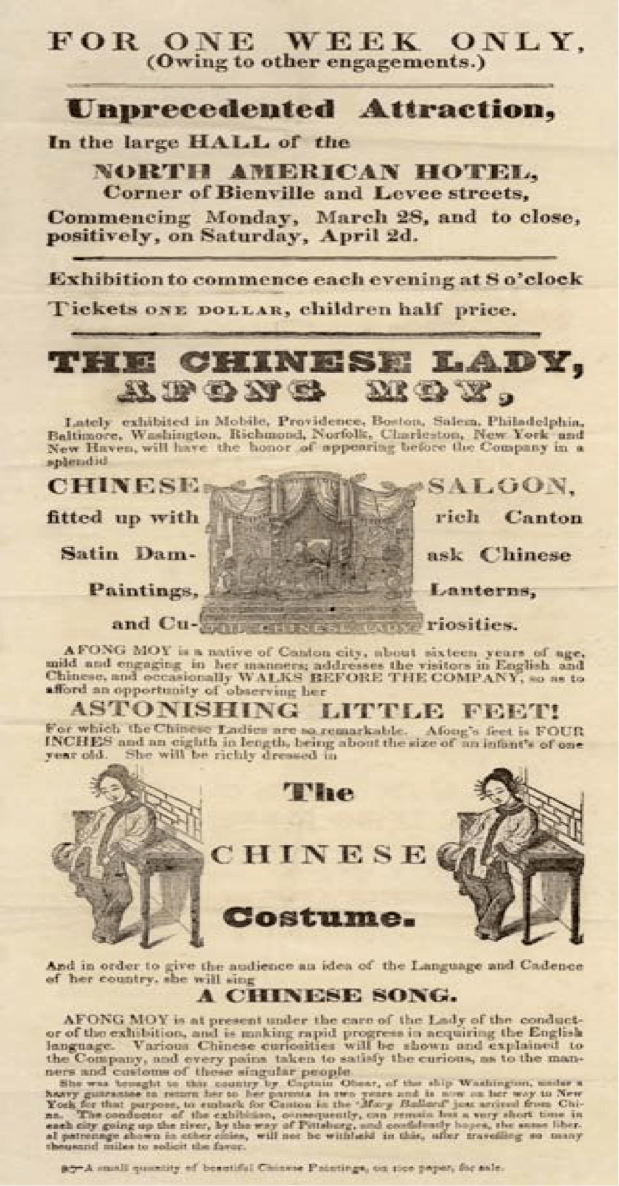

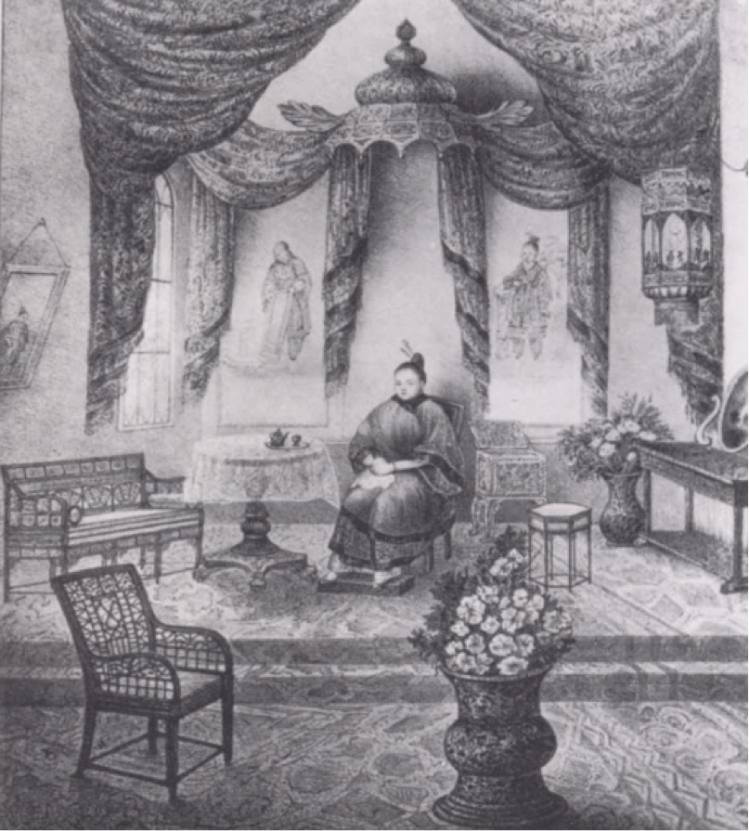

The first Asian freak I’d like to introduce is Afong Moy, believed to be the first Chinese woman to ever set foot in America in 1834 (reading suggestion: Marginal Sights: Staging the Chinese in America by James S. Moy). Her exhibition consisted of her sitting in a room full of “Chinese” finery and occasionally being forced to walk across the room on her bound feet, objectified in a way that placed her along with the Chinese paintings for sale (claiming the “Oriental” aesthetic while failing to value the actual people, doesn’t that sound all too familiar?). While we get little of her own voice—she didn’t speak English—we can find a lot of newspaper articles from the time fascinated with her fairy feet, or monstrous feet, depending on the account. Some spectators even found sexual appeal in her limited movement and her seeming exoticism. What is most interesting to me, however, is the cross-identification she allowed for those that came to see her. This could have been across class, as lower class spectators were encouraged to partake in the falsely crafted fantasy of being invited to join a noble Chinese woman in her extravagant Chinese parlor. Moreover, at the time there was much speculation about her bound feet being similar to corsets that Western women were forced to wear for the sake of beauty, allowing women to identify and perhaps even sympathize with her in a way that was extraordinary given the alienation of Asian bodies to happen nationwide elsewhere. She eventually disappeared without a trace, but similar Chinese women with bound feet followed (one of Barnum’s exhibitions was the “Chinese Family,” which was a group of Chinese individuals who weren’t even blood related but placed together because of their ethnicity. While problematic, perhaps in a way it forces us to conceptualize the family in non-heteronormative ways—you don’t need a mother and father and children to piece together a family. In this particular case, the woman was the centre of attraction with her bound feet, acting as a head of this fabricated family and the star of the show that could be read as disrupting patriarchal notions of family).

Next were the Siamese twins Chang and Eng, who often signed their letters collectively as ChangEng (they first arrived in America in 1829, achieved citizenship in 1839 and lived very much in the public eye until 1874). They were a sensation, and thought to be one of the most talked about figures from nineteenth century America in history. They sparked philosophical questions about individualism, something that would become a defining American characteristic (the brotherhood they shared was admirable, but many speculated how horrible it must be to be attached to someone else and how they complicated notions of individual subjectivity. Note that the brothers were on very good terms and refused multiple times to be surgically separated). Chang and Eng pioneered the way to what could be considered a successful Asian immigrant story by achieving citizenship, owning property, and enjoying financial success, even though there are problematic aspects of their lives like their relationship to slavery. There are so many books on the lives of Chang and Eng I won’t go into too much detail here, but I suggest The Lives of Chang and Eng: Siam’s Twins in Nineteenth-Century America by Joseph Andrew Orser or Chang and Eng Reconnected: The Original Siamese Twins in American culture by Cynthia Wu that does a lovely job of tracing the cultural impact they have on Asian American literature even today.

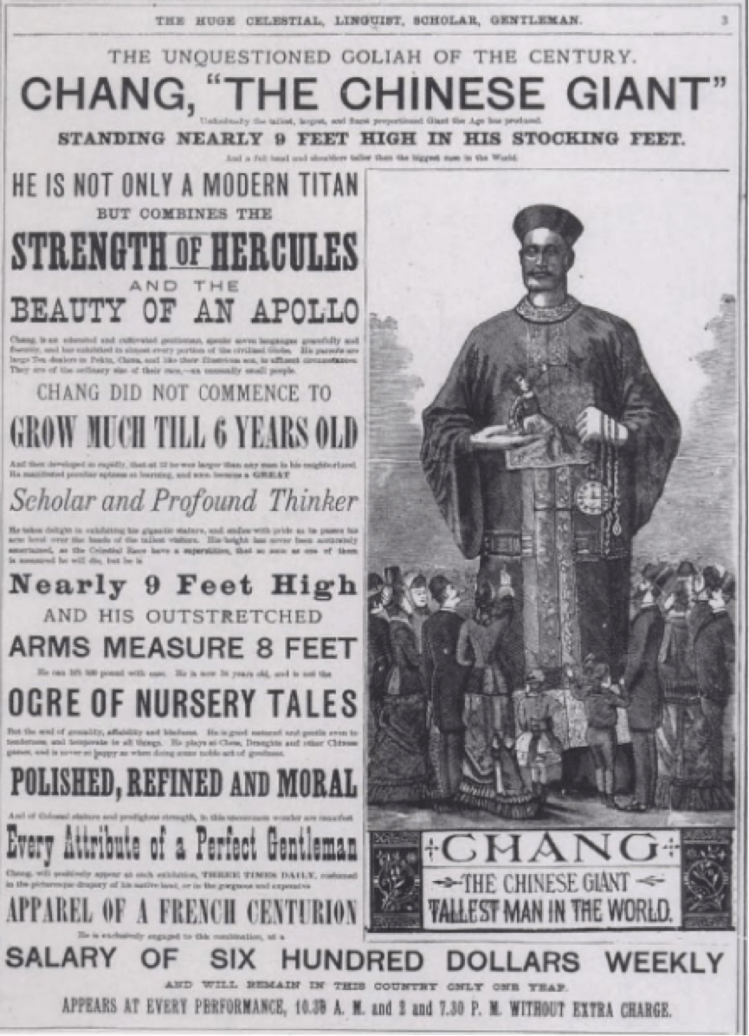

Finally, and possibly my favourite, is Chang the Giant. Presented as a Chinese gentleman, he toured England and other parts of Europe (as many of the other freaks did too, though most ended up back in America) before coming to the U.S. around 1882. Contrary to the savage imagery associated with Asians in the Yellow Peril, or the immigrant laborers who flooded into the U.S. to help build railroads seen as unwanted competition by other workers, he was depicted as a scholar who could speak several languages and was a friend to all. In fact, he was so popular with the ladies that people were constantly asking about his availability, and his initial Chinese wife he toured with is thought to be a fake one to keep all the romantic interest at bay. Chang supposedly has his own autobiography from 1866, though it’s reported to be a translation from Chinese and most likely a fictional account someone wrote as a pamphlet to hand out at his exhibitions. From this autobiography though, which suspiciously sounds like propaganda, he champions everlasting friendship between the East and West. He may have helped the public momentarily see a possible friendship and coexistence with those from the East, even amidst growing hostility against Asian immigrants. Eventually, he retired and married a white Australian woman (yay transpacific relevance!), moving to China and then England to spend the rest of his days as the owner of a teashop. (Fun fact, he was often exhibited with a “Chinese dwarf” called Che Meh for contrast, who apparently wasn’t even Chinese but a Jewish man from England who paraded around in Chinese garments).

To my knowledge, these three were the most prominent Asian freaks on display in the nineteenth century. I realize that the Asian freaks here are all Chinese (the Siamese twins were said to be ethnically Chinese even if they were brought over from Siam), but that is because of the little contact America had with other Asian countries at the time— Americans often conflated Asia and China during this period anyway—and there were no other Asian freaks from different backgrounds that I could find (I would love to learn more about other historical Asian “freaks” or performers in the future, if they do exist!). I wrote a 30 page paper about these three particular figures so I could ramble on for a lot longer on Chang and Eng, Afong Moy, and Chang the Giant alone, but I hope they were interesting to anyone reading this because they sure were to me. Although my research interests mostly lie in contemporary literature, I found it really fun having to sift through old archives of photographs, pamphlets and news articles. And I hope we can think about these figures not with interest in them because they are spectacles to gawk at, but for the impact they had on American culture and how we can find places of their own agency in the ways they tried to make a living for themselves in America through various strategic modes of identification. Moreover, I love seeing the long and complicated history behind Asian immigrants and Asian presence in America, which I feel is often limited to the twentieth century when an Asian American identity truly began to form.

V interesting. V v interesing. Please buy a mic too thanks.

LikeLike