Since I’m feeling far too lazy to write a whole new post, I thought I would share a course that I had to design for one of my classes the past semester. It was a fun project and the first time I was asked to create my own syllabus, course materials, and a week’s worth of lesson plans intended for an undergraduate literature course (usually any assignments I am asked to complete for my graduate courses are things like book reports, book reviews, class presentations, and papers). Since it was my first time designing my own course completely independently, the course below still has a lot of flaws and probably reflects a far too ambitious reading load. I imagined this course to be an upper-level undergraduate literature seminar. I hope I have the opportunity to teach a course like this in the near future and hope someone finds this post useful for seeing some of the elements you need to think about when designing your own course—or at the very least, someone is able to take away some reading suggestions if they are interested in speculative fiction. I’ve removed all the sections describing university policies and directing students to university resources.

ENGL 4XX: Invasion Nation

Spring 2020, MTW

Instructor:

Contact:

Office Location:

Office Hours:

Classroom:

Class Time:

Course Description

“One resists the invasion of armies; one does not resist the invasion of ideas.” — Victor Hugo

The threat of invasion is often imagined as a challenge to the nation to protect its borders, citizens, and even ideology. Whether from viruses, human invaders, or alien life forms, the various ways such anxieties are projected onto fiction reveal what kind of invasions may be envisioned as most threatening or already close to our reality. The examination of possible responses to disastrous invasions also helps us question the extent of state power and further troubles our understanding of nationhood: how did similar invasions unfold in the nation’s history? Who and what is considered to be a danger to the nation? What happens in catastrophes that become transnational? In light of the recent coronavirus pandemic, which highlights the extent of globalization, different national policies, and the racialization of disasters, these questions are now more relevant than ever. This course will look at various invasions in contemporary American works of fiction, although it won’t be limited to the geographical space of the United States as the only nation under potential attack.

The course will be divided into four units as we explore invasions from the plausible to the fantastical. The first unit will be looking at infectious invasions of imagined viruses and diseases. The next unit will look at alien invasions, whether taking place on Earth or in outer space. The third unit will be on environmental invasions, which will examine both how humans destroy and are attacked by the environment around them. The last unit will be on invasions of reproductive freedom. After contextualizing each text in relevant histories and conversations, we will work together to explore how society’s organizational structures are reconstructed and reimagined in the face of these various dangers.

Course Objectives

This course is an upper-level seminar focused on contemporary American literature. While no prior knowledge about contemporary American literature is required, this is a reading-heavy course that I hope will facilitate collaborative discussions. Completion of the assigned readings is necessary to engage meaningfully in class discussions and produce quality writing for assignments. Over the course of the semester, our goal will be to develop:

- An understanding of the role of literature in reproducing, highlighting, or critiquing national anxieties and the particular affordances of various fictional genres (e.g. speculative fiction, alternative histories, film, short stories).

- Skills in close reading and literary analysis demonstrated orally and in writing, with the aim to help build your confidence as a critical thinker, reader, and writer.

- The ability to engage with appropriate historical context and critical conversations/concepts (including but not limited to discourses in biopolitics, Afrofuturism, feminisms, or ethnic studies) to help you think about the course’s interests in nationhood, citizenship, and belonging.

Required Texts

***I encourage you to find the books below in whatever format is most accessible to you, whether buying your own physical copy (all books should be available new and used on websites like Amazon), obtaining an ebook, or borrowing from the library.

1) Infectious Invasions

- Dread Nation, Justina Ireland (ISBN: 978-0062570611) (464 pages)

- American Zombie, Grace Lee (film, 96 minutes)

- The Ragdoll Plagues, Alejandro Morales (ISBN 978-1558851047) (200 pages)

- Severance, Ling Ma (ISBN 978-1250214997) (205 pages)

2) Alien Invasions

- Intro to Alien Invasion, Owen King, Mark Jude Poirier, Nancy Ahn (ISBN 978-1476763408) (graphic novel, 224 pages)

- Dawn (Book One of the Xenogenesis Trilogy), Octavia Butler (ISBN 978-0446603775) (256 pages)

- Ancillary Justice, Ann Leckie, (ISBN 978-0316246620) (409 pages)

- “Story of Your Life,” Ted Chiang (short story available online on Canvas, 39 pages)

3) Environmental Invasions

- Area X: The Southern Reach Trilogy, Jeff VanderMeer (ISBN 978-0374261177) (608 pages)

- The Windup Girl, Paolo Bacigalupi (ISBN 978-1597808217) (480 pages)

- Octavia’s Brood: Science Fiction Stories from Social Justice Movements, edited by adrienne mare brown and Walidah Imarisha (ISBN: 9781849352093) (312 pages)

4) Invasions of Reproductive Freedom

- Future Home of the Living God by Louise Erdrich (ISBN 978-0062694065) (288 pages)

- Book of Etta (Second book in The Road to Nowhere series), Meg Elison, (316 pages)

- Rosemary’s Baby, Roman Polanski (film, 136 minutes)

Course Requirements

| GRADED WORK | PERCENTAGE |

| Class Participation and Quizzes | 20% |

| Reading Response 1 (2 pages) | 10% |

| Reading Response 2 (2 pages) | 10% |

| Class Presentation (10-15 minutes) | 10% |

| Midterm Paper (4-5 pages) | 20% |

| Final Paper (6-8 pages) | 30% |

Class Participation and Quizzes (20%)

Class participation includes general engagement with the course, covering regular attendance, coming to class on time, adherence to deadlines, completion of readings, and productive participation in discussions and class activities. Because this is a smaller seminar, I encourage you to engage in conversation as much as possible and to the best of your ability. Everyone has different comfort levels when it comes to speaking in front of others so if this concerns you, please let me know and we can discuss strategies together.

After introducing each new text, we will have short quizzes to check the completion of readings and basic reading comprehension. This should not take more than a few minutes and the quizzes will be centered around questions about plot, characters, and themes that should be easy to answer if you have read all the material. Quizzes will be marked with a check minus, check, or check plus.

Reading Responses (2 x 10% = 20%)

For this course, you will write two reading responses on any two primary texts of your choice. Before each unit, I will distribute possible prompts relevant to the unit to help you focus your ideas. Although which texts you decide to write on are up to you, I want you to spread out the responses across two different units. These do not have to be polished papers but should be proofread and convey a coherent line of thought; they are an opportunity to practice close analysis and explore ideas that you might want to pursue for the longer paper assignments. You do not have to notify me in advance about when you want to submit a reading response, but you should submit each one before the class period we are first introducing the text you have chosen to write on. Submission should be through the appropriate Canvas dropbox.

Class presentation (10%)

At the beginning of the semester, we will divide the class evenly across the four units. At the end of your assigned unit, you should give an oral report with the following components: 1) what text or theme interested you most from the unit and a tentative argument about what it may be trying to show 2) a summary of an academic journal article relevant to this interest and how it adds to our previous class discussions 3) one question you want to put forward to the class in light of your presentation. The report should be no longer than 10-15 minutes, and you should be prepared to answer questions from the class about your argument and chosen article. For the article component, we will discuss how to access the right databases together as a class and I am always available for extra assistance.

Midterm Paper (20%)

For the midterm paper, I will give you three choices: two prompts and the option to create your own question that you hope to answer (if you choose the last option, please discuss your question with me in advance). You should aim for 4-5 pages and engage thoroughly with one text. We will have peer reviews of an outline and the full paper draft.

Final Paper (30%)

For the final paper, I will give you three choices: one prompt asking you to think critically about one text, one prompt asking you to put two texts in conversation with one another, and the option to create your own question about something you want to explore (as with the midterm paper, please discuss the question with me in advance). You should aim for 6-8 pages. We will have a peer review of the final paper proposal.

***All papers should follow the most recent MLA guidelines—submitted in 12-point, Times New Roman (TNR) font, double-spaced, with one-inch margins. All written work should be submitted electronically through Canvas. Please double-check that your file is successfully uploaded.

Grading

Your assignment grades will be available on Canvas throughout the semester so you can keep track of your performance. Before you reach out to discuss a grade, please wait 24 hours after you receive feedback on an assignment so you have enough time to read and process my comments.

All assignments in this course will receive a letter grade, following the University grading system. Grades in the A band will reflect excellent work, grades in the B band good work, grades in the C band satisfactory work, D grades unsatisfactory work, and F grades unacceptable work. In the case of a late submission without consulting me in advance, I will dock half a grade for each day after the deadline the assignment is received.

Course Policies and Campus Resources (removed)

Course Schedule

***All assigned readings should be completed by the day the text is first introduced. Additional secondary readings may be introduced throughout the semester.

***Topics are tentative and offer possible concepts to be explored.

Week One

| Date | Topic | Readings Due | Work Due |

| 1/13 Mon | Course intro | – | – |

| UNIT | ONE | INFECTIOUS | INVASIONS |

| 1/15 Wed | Intro to unit

Historical context and alternative histories |

Justina Ireland’s Dread Nation | – |

| 1/17 Fri | Race and conflicting narratives | – | – |

Week Two

| Date | Topic | Readings Due | Work Due |

| 1/20 Mon | Afrofuturism and zombie preparedness | – | – |

| 1/22 Wed | The masses | Watch Grace Lee’s American Zombie | – |

| 1/24 Fri | The individual | – | – |

Week Three

| Date | Topic | Readings Due | Work Due |

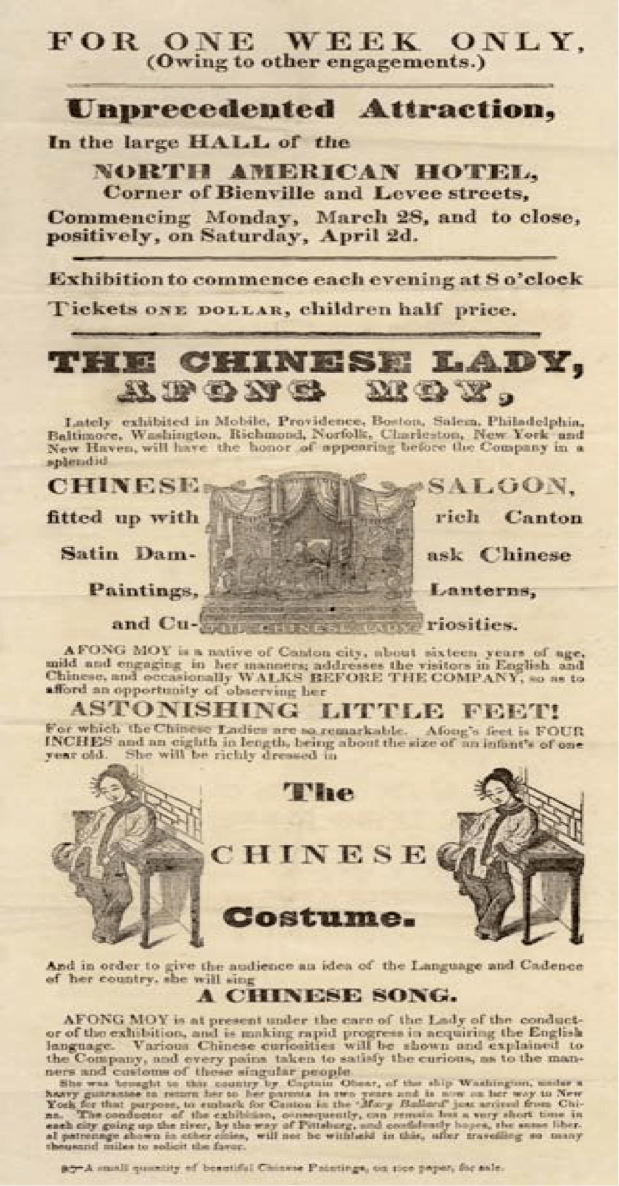

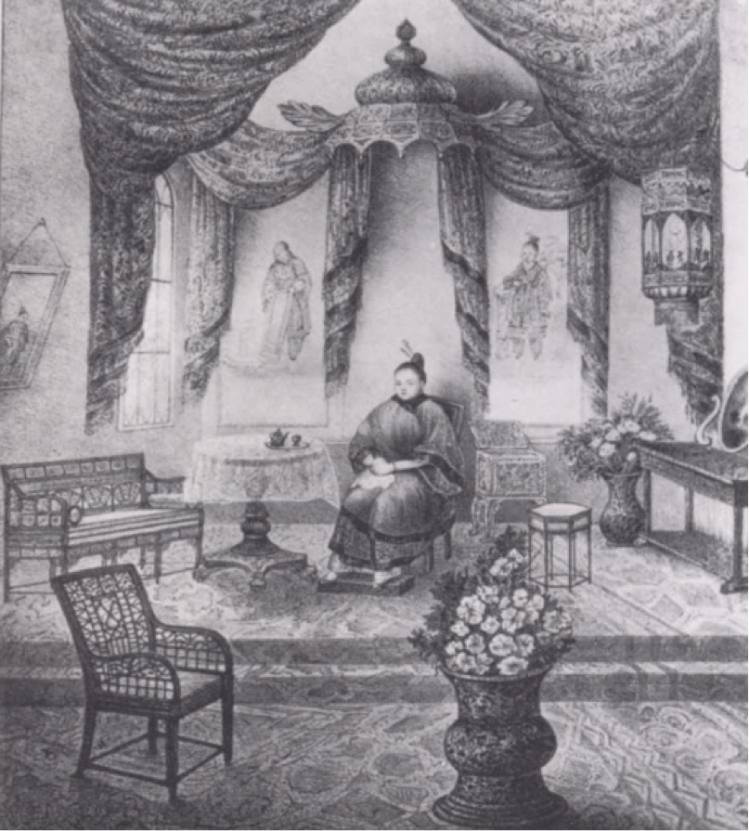

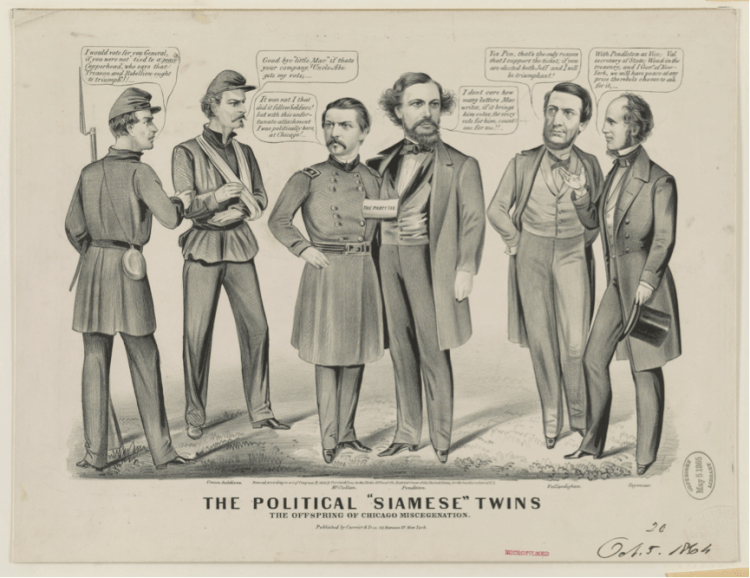

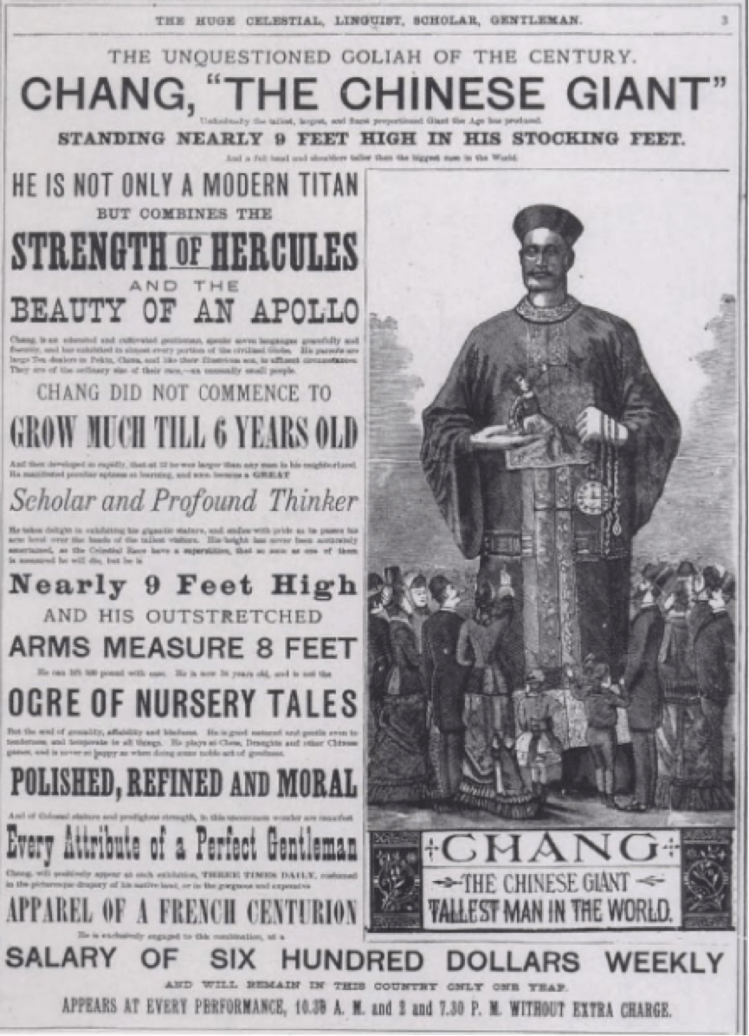

| 1/27 Mon | Historical context and colonial history | Alejandro Morales’ The Ragdoll Plagues | – |

| 1/29 Wed | AIDS and reproduction | – | – |

| 1/31 Fri | Techno-Orientalism | – | – |

Week Four

| Date | Topic | Readings Due | Work Due |

| 2/3 Mon | Historical context and Asian Am literature | Ling Ma’s Severance | – |

| 2/5 Wed | Transnationalism | – | – |

| 2/7 Fri | Capitalism and zombification | – | – |

Week Five

| Date | Topic | Readings Due | Work Due |

| 2/10 Mon | Unit wrap-up | – | Assigned unit presentations |

| UNIT | TWO | ALIEN | INVASIONS |

| 2/12 Wed | Intro to new unit

Historical context and genre of the graphic novel |

Owen King, Mark Jude Poirier, Nancy Ahn’s Intro to Alien Invasion | – |

| 2/14 Fri | Institutions and education | – | – |

Week Six

| Date | Topic | Readings Due | Work Due |

| 2/17 Mon | Historical and author background | Octavia Butler’s Dawn | – |

| 2/19 Wed | Consent and colonialism | – | – |

| 2/21 Fri | Identity | – | – |

Week Seven

| Date | Topic | Readings Due | Work Due |

| 2/24 Mon | Context and narrator (Justice) | Anne Leckie’s Ancillary Justice | – |

| 2/26 Wed | Social hierarchies (Propriety) | – | – |

| 2/28 Fri | Ethics and embodiment (Benefit) | – | – |

Week Eight

| Date | Topic | Readings Due | Work Due |

| 3/2 Mon | Narration and temporality | Ted Chiang’s A Story of Your Life | *Recommend having at least one reading response submitted by this point |

| 3/4 Wed | Unit wrap-up | – | Assigned unit presentations |

| 3/6 Fri | Midterm paper outline peer review | – | Midterm paper outline |

SPRING BREAK: NO CLASSES MARCH 9TH-13TH

Week Nine

| Date | Topic | Readings Due | Work Due |

| UNIT | THREE | ENVIRONMENTAL | INVASIONS |

| 3/16 Mon | Midterm paper draft workshop | – | Midterm paper draft |

| 3/18 Wed | Intro to new unit

Recordkeeping and narration

|

Jeff VanderMeer’s Annihilation (Area X Book 1) | – |

| 3/20 Fri | Institutional authority and categorization | Jeff VanderMeer’s Authority (Area X Book 2) | – |

Week Ten

| Date | Topic | Readings Due | Work Due |

| 3/23 Mon | Science vs. Séance

|

Jeff VanderMeer’s Acceptance (Area X Book 3) | Midterm paper due |

| 3/25 Wed | The Area X Trilogy as a whole

Slow violence Hyperobject |

– | – |

| 3/27 Fri | Storytelling as activism | Select stories from Octavia’s Brood (TBD) | – |

Week Eleven

| Date | Topic | Readings Due | Work Due |

| 3/30 Mon | Context and genetic modification

|

Paolo Bacigalupi’s The Windup Girl | – |

| 4/1 Wed | Utopia and refuge | – | – |

| 4/3 Fri | The cyborg and the corporation | – | – |

Week Twelve

| Date | Topic | Readings Due | Work Due |

| 4/6 Mon | Unit wrap-up

|

– | Assigned unit presentations |

| UNIT four | Invasions of | reproductive | freedom |

| 4/8 Wed | Intro to new unit

Context and evolutionary science |

Louise Erdrich’s Future Home of the Living God | – |

| 4/10 Fri | Surveillance and religion | – | – |

Week Thirteen

| Date | Topic | Readings Due | Work Due |

| 4/13 Mon | Sovereignty | – | – |

| 4/15 Wed | Final paper proposal workshop | – | Final paper proposal |

| 4/17 Fri | Make up/extra day to meet with me about final paper ideas | – | – |

Week Fourteen

| Date | Topic | Readings Due | Work Due |

| 4/20 Mon | Context and lore

|

Meg Elison’s The Book of Etta | – |

| 4/22 Wed | Communities and family formations | – | – |

| 4/24 Fri | Gender identity | – | – |

Week Fifteen

| Date | Topic | Readings Due | Work Due |

| 4/27 Mon | Context: revisiting in the era of #MeToo

|

Watch Roman Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby | – |

| 4/29 Wed | Unit reflection | – | Assigned unit presentations |

| 5/1 Fri | Course wrap-up | – | – |

***Final papers due Wednesday of finals week, 5/6.